The final version of the NPPF will need to take action in four key policy areas to be fit for purpose, says the TCPA’s Hugh Ellis

The TCPA’s response to the government’s July consultation on proposed reforms to the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) is framed by two high level assumptions.

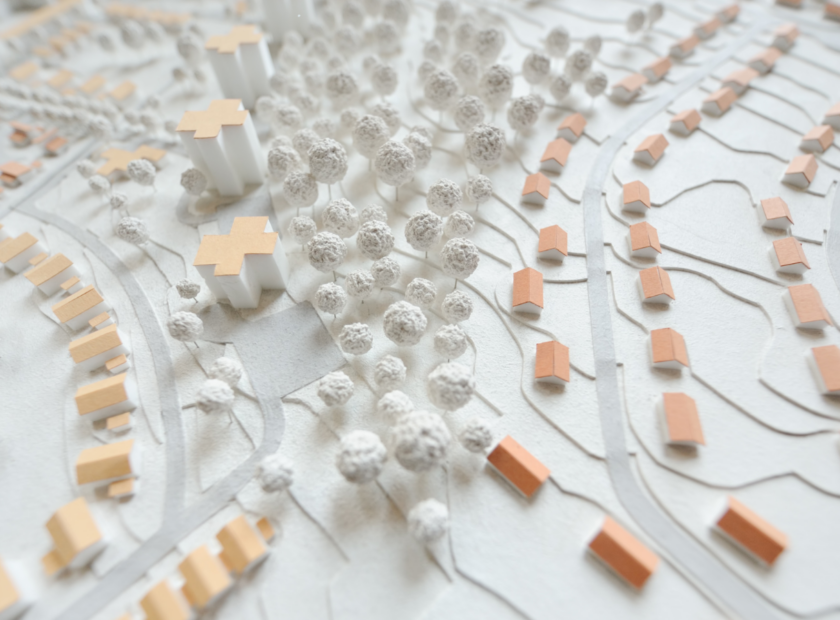

The first is that this nation needs a hopeful vision of healthy and inclusive communities that can help us navigate the health, housing, nature and climate crises in way which is inclusive and democratic. That remains the central purpose of town planning.

Second, we understand that planning is the solution to the complex job of developing our communities in ways that meet economic, environmental and social goals in a democratic context. Our current planning system has many problems, not least its lack of capacity, but it is not, and has never been, the root cause of the housing crisis. That crisis is above all the product of a decades long failure to invest in affordable homes of all tenures and particularly in social rent.

This nation needs a hopeful vision of healthy and inclusive communities that can help us navigate the health, housing, nature and climate crises in way which is inclusive and democratic. That remains the central purpose of town planning.

It is with this positive vision of the role that town planning can have in the future of our nation that the TCPA welcomed the government’s consultation on the draft NPPF for England. Detailed textual changes have been published along with a consultation document which provides an opportunity to embed vital outcomes on health, climate change and social inclusion into a new and progressive policy direction for local planning. So, what do we see as the defining tests of the final policy framework that is due to be published before the end of the year?

The initial test is to ensure that the objectives of national policy are based upon a sound analysis of the problems we are trying to solve. We need a more sophisticated view of the problems restricting housing supply. In January of this year, the TCPA set out its analysis of the housing crisis focusing on two systemic problems. The first was an overwhelming lack investment by government in homes for social rent. The second was the repeated mistake of the previous four decades of planning reform in focusing on the generation of planning consents for housing with no effective strategy for their delivery. As a result, we should be clear that setting mandatory housing targets and strengthening the presumption in favour of development has no automatic relationship with increasing housing supply. That requires complex intervention across a range of issues from the supply chain to infrastructure investment but above all actions to modernise our archaic housing development model.

Planning authorities must of course have a rational and evidence-based assessment of their housing needs, but setting targets at the national level is the easy part of the process. The real work is defining a detailed mechanism for delivering them which accepts that an increasing number of local planning authorities are severely constrained by a range of issues including rapidly increasing flood risk.

The new policy content in the NPPF on strategic planning is extremely welcome, as is the setting up of a new towns task force whose focus must be to unlock practical delivery. However, the final version of the NPPF needs to make clear that while planning authorities must have a rational and evidence assessment of housing need, they must also have detailed policy pathways to cooperation and particularly to identify strategic housing opportunities, including new towns, to take the pressure away from constrained areas.

In considering the wider content of the NPPF it is important to recognise that while housing delivery is a vital priority, so too are a range of other issues around healthy, inclusive and climate resilient communities. The consultation document has left the door open to progress on a number of issues, but for the TCPA the final version of the NPPF will need to take action in four further policy areas to be fit for purpose:

In considering the wider content of the NPPF it is important to recognise that while housing delivery is a vital priority, so too are a range of other issues around healthy, inclusive and climate resilient communities.

The purpose of planning

The NPPF must start with a clear statement that sets out the overall purpose and objectives of the planning system in England. That purpose must be the achievement of sustainable development in the public interest.

Sustainable development has a defined meaning, not least in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These goals, which reflect everything from the need for decent homes to gender equality and human health, all relate to how we allocate resources and therefore are centrally important to all aspects of town planning.

The final version of the NPPF must, as a minimum, restore sustainable development as a meaningful goal in plan making by making clear that the UN SDGs are directly relevant to plan making and decision taking. Sustainable development is, after all, the only development idea we have that has any chance of securing human wellbeing and planetary survival.

The final version of the NPPF must, as a minimum, restore sustainable development as a meaningful goal in plan making.

Health and wellbeing

The NPPF must prioritise the positive promotion of public health and wellbeing and acknowledge the intimate connection between health outcomes and the design and operation of the built environment in tackling health inequalities. Town planning has a major part to play in creating homes and neighbourhoods which enable healthy living, with vital long term cost reductions to the NHS and social care budgets. There needs to be an equal focus on reducing health inequality which means national policy supporting local action for those neighbourhoods suffering the worst health outcomes.

Climate mitigation and adaptation

The NPPF must identify climate change as the government’s first priority for the planning system. This is simply because the climate crisis stands between us and all the other key delivery priorities, not least the delivery of housing. An effective carbon forecasting method for local plans, to ensure they are aligned with the latest carbon budget, is vital in delivering on our statutory climate targets. There is nothing complex about such an approach, which some planning authorities have been developing and which consultants have been supporting.

Major changes are also required for adaptation, with much greater priority given to overheating and to the growing challenges of coastal and surface water flood risk. There is a particular need to reform the sequential and exception tests in the areas of most severe coastal flood risk and to reflect the need for the wholesale relocation of some communities.

People

It is even more important, given the recent far-right violence on our streets, that national planning policy supports a hopeful offer for people. An offer which goes far beyond traditional ideas of local government devolution to give real agency to those supporting community development at neighbourhood level.

This offer needs to be in two parts. The first is to prioritise the voice of people in all parts of the decision-making process, making clear that public participation is a democratic right but also a way of improving the quality of decisions and rebuilding public trust.

The second part of the offer is to empower and enable communities to shape their own futures by positive support for the tens of thousands of locally-led initiatives on issues such as climate, local food and community housing. In an era of tight budgets, the government needs communities to be active partners in helping drive solutions from combating loneliness to community led flood defence. Communities need local plans that care about their aspirations for climate change, nature recovery and community energy. That means national policy being sensitive to the needs of communities, including through unlocking site allocations which can transform local action.

The final version of the NPPF must respond to these challenges or risk reinforcing the failures of the past. We are confident that the new government will fully seize the opportunity of a new and progressive national planning policy. The issues set out in this blog represent the bare minimum of policy change necessary to satisfy that ambition. We need a new direction for all our communities, one which offers a real sense of hopefulness and one which offers them the practical tools to navigate the multiple challenges of 21st century living.