To ensure better and more inclusive health outcomes, the TCPA has identified 12 Healthy Homes principles that all new housing developments must provide. Each month, this blog series explores one of the principles.

Healthy Homes principle: Affordable homes and security of tenure

It is shocking that in 2024, eighty children and babies died in temporary accommodation in England, linked the poor housing conditions they were living in (Shared Health Foundation, 2025). The health challenge arising from unaffordable and insecure homes has become increasingly pressing in the last decade, with homeownership and rental costs rising far beyond what many can afford.

Despite its importance to health outcomes, there is no single definition of ‘affordable housing’ (Parliament UK, 2024). Yet government policies have been criticised for failing to provide genuinely affordable options based on local income levels rather than market rates (ONS, 2023 and ONS, 2024). House prices have surged relative to earnings and average house prices in England are now 8.3 times the average annual income levels (Homes England, 2023, and Parliament UK, 2024).

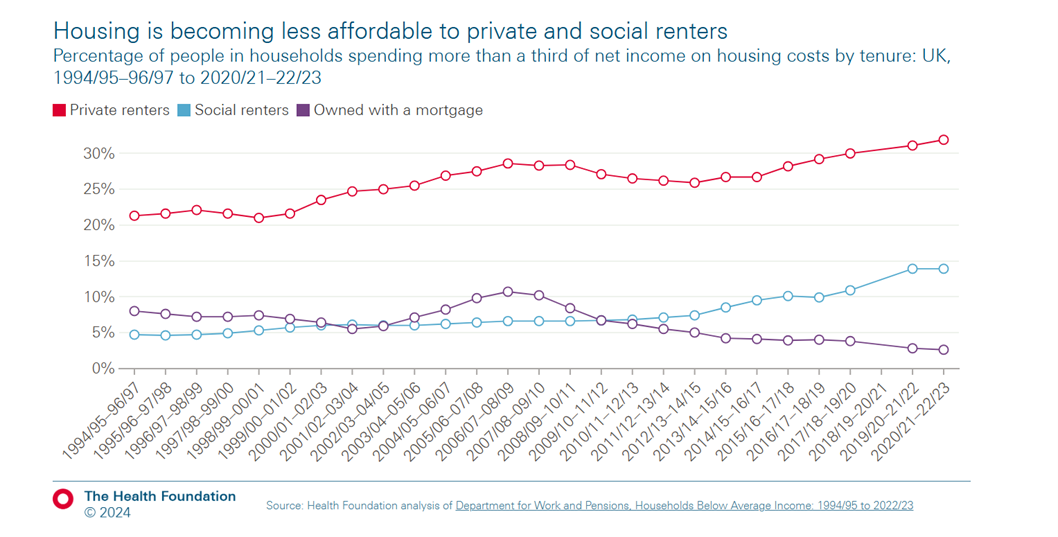

At the same time, the supply of social and affordable rented homes has shrunk. Between 2012 and 2022, England saw a net loss of 209,000 social rent homes, and over 1.2 million households were on council waiting lists for affordable rental housing in March 2022 (Parliament UK, 2024). In 2021/22, private renters spent a third of their income on housing, with London renters paying over half their monthly earnings on rent (Medact, 2023). It is important to highlight those groups most affected by the housing crisis. People of colour are more likely to live in poor-quality, overcrowded, unaffordable homes, particularly in the private rental sector, and are more likely to experience homelessness (Health Foundation, 2025). Affordability has been especially hard for young people, 17% of people aged 16 to 24 and 13% of those aged 25 to 34 spent over a third of their income on housing costs in 2020/21–22/23 (Health Foundation, 2025). In addition, there is a significant shortage of affordable and accessible housing for disabled people across the UK, with 1 in 3 disabled people in private rented properties living in unsuitable accommodation; and 1 in 5 disabled people in social housing living in unsuitable accommodation (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2024).

Exorbitant housing costs have pushed many households to breaking point; a quarter of people on the lowest incomes spend an unmanageable portion of their earnings on housing (ONS, 2024). More than 26,000 households faced homelessness in 2023/24, as a result of Section 21 ‘no fault’ evictions which permit landlords to remove tenants with minimal two-month notice and without a clear reason.

The housing crisis and its impact on health

The financial strain of unaffordable housing is a major health burden. High housing costs force many households to cut back on essentials such as food and heating, leading to malnutrition and fuel poverty, both of which have serious health consequences, particularly for children (CASE, 2024). The stress of unaffordable housing is also well-documented, with renters facing higher rates of anxiety and sleep disturbance (Medact, 2023).

Homes that are unaffordable and insecure, in terms of resident rights have been shown to be directly linked to poor physical and mental health outcomes. The cost-of-living crisis has exacerbated the poor conditions faced by many households, with rising rents forcing individuals and families into overcrowded, damp, and inadequate housing, or, in the worst cases, homelessness. Indeed, Crisis warned that 300,000 households could face homelessness if urgent action was not taken (Crisis, 2022).

With rates of homelessness on the rise, more families are being placed in temporary accommodation, often in unsuitable hotels or B&Bs. Households in temporary accommodation now exceeds 123,000 (LGA 2025). Temporary arrangements place often vulnerable individuals and families in extremely unstable conditions, disrupting employment, education, and access to healthcare. The Shared Health Foundation state that homelessness and poverty are significant contributing factors towards an increased risk of mortality (Shared Health Foundation, 2025).

Long-term solutions must focus on increasing the supply of truly affordable, high-quality homes.

Urgent action is needed to address the affordability crisis and its health impacts. Proposals to end Section 21 evictions, reform of Right to Buy and private rental legislation, could provide tenants with greater security, but delays in implementation leave many still vulnerable (The Health Foundation, 2023). Long-term solutions must focus on increasing the supply of truly affordable, high-quality homes.

Permitted Development ‘homes’ harming affordability and security

The conversion of commercial buildings into housing without a full planning application via ‘Permitted Development’ has meant a relaxation of rules cutting out placemaking requirements and avoiding certain building regulations that specifically aim to improve the quality of homes and neighbourhoods. It also allows developers to avoid paying the usual financial contributions (via Section 106 agreements) to councils which contribute towards affordable housing and community amenities (TCPA, 2024). As a result, PDR conversions are undermining local affordable housing supply and healthy placemaking, exacerbating the existing shortage and poor conditions people are living in.

Good practice case studies

Woodberry Down, Hackney

The redevelopment of Woodberry Down estate in Hackney, London, aims to deliver 5,500 new homes across eight phases, with 41% designated as affordable housing, comprising 20% social rent and 21% shared ownership. Hackney Council opted for a cross-subsidy model to regenerate the existing estate. They leveraged private sector investment through new private rental housing to fund the delivery of new affordable homes. With £27 million in public funding secured after the financial crisis, and a £1 billion private investment from Berkeley Homes, the project ensures that affordable housing remains a key component of the regeneration while improving overall housing quality (Place Alliance, 2025).

Woodberry Down, Hackney. Credit: Place Alliance

Oak Priory, Stoke-on-Trent

Oak Priory is a 175-home retirement village developed through a public-private partnership between Stoke-on-Trent Council and the Sapphire Consortium, using a private finance initiative (PFI). Located in a deprived area, the project delivers 100% affordable extra-care housing through social rent and shared ownership, making high-quality, supportive living accessible to those in need (Place Alliance, 2025).

Oak Priory, Stoke on Trent. Credit: Place Alliance

The latest Place Alliance report reviewing 20 housing projects in deprived areas around England indicates it is possible to deliver good quality heathy and affordable new homes in less affluent areas. However, systemic barriers need to be addressed to see wider progress, including on the Right to Buy council homes and on reform of private rental sector. The government’s forthcoming comprehensive spending review provides an opportunity for government to invest more substantially in the sector, including meeting specialist housing needs (CIH, 2025), and enable local authorities to take a lead in delivering the affordable and healthy homes this country urgently needs (LGA, 2025).

Providing a diverse mix of housing types and tenures, and homes that are genuinely affordable, is a central Healthy Homes Principle in the Campaign for Healthy Homes. To promote thriving healthy and inclusive communities, a fundamentally different approach to delivering new homes is required, one that puts the quality and affordability of new homes and communities as highly as the quantity that are delivered.

You can read our other Healthy Homes Principles blogs here